Well-known for their vocal mimicry, parrots can articulate words, repeat phrases and sometimes even create their own sentences.

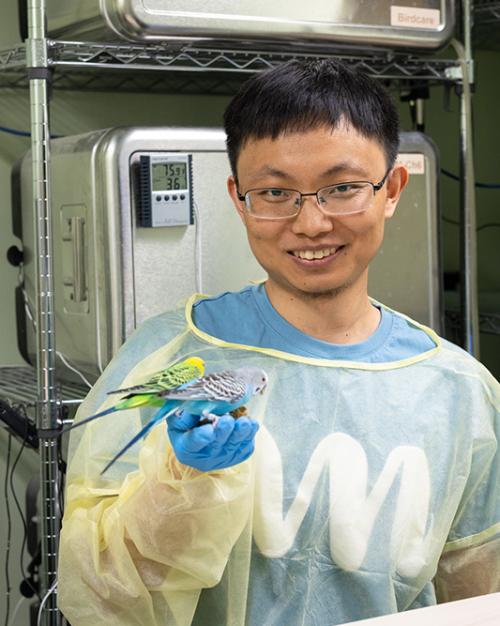

“This ability is very rare in animals,” said Zhilei Zhao, Klarman Fellow in neurobiology and behavior in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S). “Very few animals can do this, including dolphins, some whales and some birds. I’m trying to understand how this is achieved in the brain of parrots.”

By studying the brain mechanisms of vocal learning in domesticated budgerigar parrots (popularly known as parakeets or budgies), Zhao explores how social learning is implemented in the brain.

“Zhilei is that rare scientist who can really bridge fields,” said Jesse Goldberg, associate professor of neurobiology and behavior (A&S), Zhao’s faculty host. “His Ph.D. work on the mechanisms by which mosquitos use smell to home in on humans combined true breakthroughs in three distinct fields: genetics, neuroscience, and chemistry. He engineered one of the first transgenic mosquitoes, used cutting-edge neurotechnological tools to visualize the neural activity of mosquito olfactory systems responding to unique aspects of human scent, and finally used clever tricks of chemistry to figure out precisely what mosquitoes find appealing. It was a landmark set of experiments.”

After his Ph.D., Zhao turned from the instinct-driven behavior of insects toward a more cognitive, flexible behavior involved in language. The concept of flexibility links human and parrot language behaviors, Zhao said, and can be seen in a comparison with less flexible songbirds.

“The zebra finch learns one song, the courtship song, from their father. But they only learn one song all their lives. It’s different for parrots – parrots can learn continuously. And once they learn, they can do combinations of different words.”

It’s another level of behavior, comparable with humans. Yet researchers have found that the neurocircuitry for vocal learning in the finch brain is similar to the circuitry in humans, Zhao said. The three-way human-parrot-finch comparison has revealed interesting puzzles.

In a recent project, Zhao and colleagues focused on a region of the parrot brain important to vocal learning and similar to the finch brain. But in experiments, the analogous region that’s unnecessary for vocal production in the finch actually caused parrots to lose vocal memory and individual signature.

This suggests that the neuro mechanisms in parrots and finches, although superficially similar, are actually quite different, Zhao said. A further hypothesis is that maybe one brain mechanism is more similar between humans and parrots compared to the finch.

In another project, Zhao and fellow researchers are trying to correlate parrots’ songs with their gestures by analyzing video and audio recordings of them, captured through a one-way mirror.

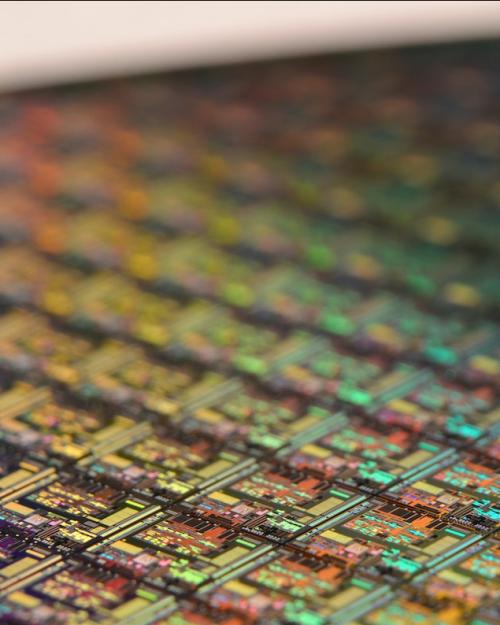

With research funds provided by the Klarman fellowship, Zhao is developing artificial intelligence to analyze parrot sounds, in close collaboration with Itai Cohen, professor of physics (A&S).

“The scale is much smaller than ChatGPT, but it’s the same architecture,” Zhao said. “Sometimes the bird will sing for half an hour continuously. Every time they sing, it’s different, and there are different elements in the song. It looks very complex. If there are rules, can we predict what the bird will sing next based on the history of singing?”

“New AI-based methods are incredible at pattern recognition and complex datasets,” Goldberg said. “Zhilei is already making discoveries about how they are truly different from songbirds and how they are able to express their individuality with one another.”

Zhao is well on his way to learning what are they talking about, what are they doing, why and how, Goldberg said. Together, they are studying aspects of parrot communication at the core of the birds’ social networks.

The renowned Lab of Ornithology makes Cornell a great place to study bird behavior, said Zhao, who attends events and interacts with researchers there.

Zhao also works with Michael Sheehan, the Nancy and Peter Meinig Family Investigator in the Life Sciences, associate professor of neurobiology and behavior, who studies how wasps recognize individual wasp faces based on visual cues. Parrots recognize individuals, but it’s more based on voice, Zhao said.

The budgerigar parrots in Zhao’s lab recognize him; he visits them in their Corson Hall aviary every day, sometimes feeding them millet from his hand as a treat. “It’s like ice cream for them,” he said.